In daily development, we often encounter requirements for fuzzy search. Today, let’s briefly discuss how to implement some advanced fuzzy search using PostgreSQL.

Of course, the fuzzy search I’m talking about here isn’t the old-fashioned LIKE expressions with prefix, suffix, or bilateral fuzzy matching. Let’s start directly with a concrete example.

Problem#

Now, suppose we’ve built an app store and want to provide search functionality for users. Users can input anything, and we find all applications matching the input content, rank them, and return them to users.

Strictly speaking, this requirement actually needs a search engine, preferably using specialized software like ElasticSearch. But in practice, as long as the logic isn’t particularly complex, PostgreSQL can implement it very well.

Data#

The sample data is as follows—an application table. All irrelevant fields have been removed, leaving only an application name name as the primary key.

CREATE TABLE app(name TEXT PRIMARY KEY);

-- COPY app FROM '/tmp/app.csv';The data inside looks roughly like this, with mixed Chinese and English, totaling 1.5 million entries.

Rome travel guide, rome italy map rome tourist attractions directions to colosseum, vatican museum, offline ATAC city rome bus tram underground train maps, 罗马地图,罗马地铁,罗马火车,罗马旅行指南"""

Urban Pics - 游戏俚语词典

世界经典童话故事大全(6到12岁少年儿童睡前故事英语亲子软件) 2 - 高级版

星征服者

客房控制系统

Santa ME! - 易圣诞老人,小精灵快乐的脸效果!Input#

What users might input in the search box is roughly the same as what you would type in an app store search box: “weather,” “food delivery,” “social networking”…

The effect we want to achieve is also similar to your expectations for app store query return results. Of course, the more accurate the better, preferably ranked by relevance.

Of course, as a production-level application, it must also respond promptly. Full table scans are not acceptable—indexes must be used.

So, how do we solve this type of problem?

Solution Approaches#

There are three solution approaches for this problem:

- Pattern matching based on

LIKE - String similarity matching based on

pg_trgm - Fuzzy search based on custom tokenization and inverted indexes

LIKE Pattern Matching#

The simplest and most straightforward approach is using LIKE '%' pattern matching queries.

This is an old topic with no technical sophistication. Add percent signs before and after user input keywords, then execute queries like:

SELECT * FROM app WHERE name LIKE '%支付宝%';Prefix and suffix fuzzy queries can be accelerated through regular Btree indexes. Note that when using LIKE queries in PostgreSQL, don’t fall into the LC_COLLATE trap. For details, refer to this article: Localization and Collation Rules in PostgreSQL.

CREATE INDEX ON app(name COLLATE "C"); -- suffix fuzzy

CREATE INDEX ON app(reverse(name) COLLATE "C"); -- prefix fuzzyIf user input is very precise and clear, this approach is acceptable. Response speed is also good. But there are two problems:

Too mechanical and rigid. If an app vendor releases a name with an extra space or symbol in the original keywords, this query immediately fails.

No distance measurement. We don’t have a suitable metric to rank returned results. If several hundred results are returned without ranking, it’s hard to satisfy users.

Sometimes accuracy is still insufficient. For example, some apps do SEO by embedding various top app names into their own names to improve search rankings.

PG TRGM#

PostgreSQL comes with an extension called pg_trgm, which provides fuzzy search based on three-character trigrams.

The pg_trgm module provides functions and operators for determining alphanumeric text similarity based on trigram matching, as well as index operator classes that support fast searching for similar strings.

Usage#

-- Use trgm operators to extract keywords and create gist index

CREATE INDEX ON app USING gist (name gist_trgm_ops);The query method is also intuitive—directly use the % operator. For example, find apps related to Alipay from the app table.

SELECT name, similarity(name, '支付宝') AS sim FROM app

WHERE name % '支付宝' ORDER BY 2 DESC;

name | sim

-----------------------+------------

支付宝 - 让生活更简单 | 0.36363637

支付搜 | 0.33333334

支付社 | 0.33333334

支付啦 | 0.33333334

(4 rows)

Time: 231.872 ms

Sort (cost=177.20..177.57 rows=151 width=29) (actual time=251.969..251.970 rows=4 loops=1)

" Sort Key: (similarity(name, '支付宝'::text)) DESC"

Sort Method: quicksort Memory: 25kB

-> Index Scan using app_name_idx1 on app (cost=0.41..171.73 rows=151 width=29) (actual time=145.414..251.956 rows=4 loops=1)

Index Cond: (name % '支付宝'::text)

Planning Time: 2.331 ms

Execution Time: 252.011 msAdvantages of this approach:

- Provides string distance function

similarity, giving a quantitative measure of similarity between two strings. Therefore, results can be ranked. - Provides tokenization function

show_trgmbased on 3-character combinations. - Can use indexes to accelerate queries.

- SQL query statements are very simple and clear, index definition is also simple and straightforward, making maintenance easy.

Disadvantages of this approach:

- Poor recall rate for very short keywords (1-2 Chinese characters), especially when there’s only one character, no results can be queried

- Low execution efficiency. For example, the query above took 200ms

- Poor customizability. Can only use its own defined logic to define string similarity, and this metric’s effectiveness for Chinese is questionable (Chinese three-character word frequency is very low)

- Special requirements for

LC_CTYPE. DefaultLC_CTYPE = Ccannot correctly tokenize Chinese.

Special Issues#

The biggest problem with pg_trgm is that it cannot be used for Chinese on instances with LC_CTYPE = C. Because LC_CTYPE=C lacks some character classification definitions. Unfortunately, once LC_CTYPE is set, there’s basically no way to change it except rebuilding the database.

Generally speaking, PostgreSQL’s Locale should be set to C, or at least set the collation rule LC_COLLATE in localization rules to C, to avoid huge performance losses and functional deficiencies. But because of this “problem” with pg_trgm, you need to specify LC_CTYPE = <non-C-locale> when creating the database. LOCALEs based on i18n should theoretically all work. Common en_US and zh_CN are both usable. But note that macOS has issues with Locale support. Behaviors that rely too heavily on LOCALE reduce code portability.

Advanced Fuzzy Search#

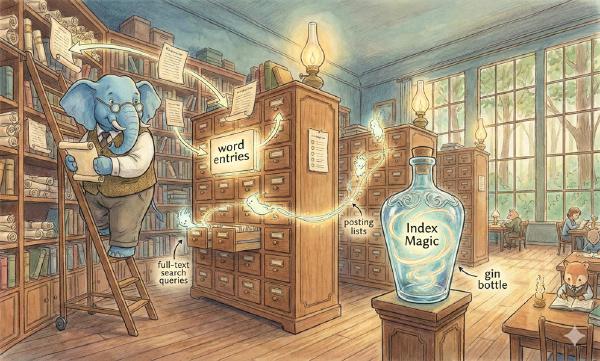

Implementing advanced fuzzy search requires two things: tokenization and inverted indexes.

Advanced fuzzy search, or full-text search, is implemented based on the following approach:

- Tokenization: During the maintenance phase, each field that needs fuzzy searching (like application names) is processed by tokenization logic into a series of keywords.

- Indexing: Build inverted indexes from keywords to table records in the database

- Querying: Break down queries into keywords similarly, then use query keywords through inverted indexes to find relevant records.

PostgreSQL has built-in tokenizers for many languages that can automatically split documents into a series of keywords for full-text search functionality. Unfortunately, Chinese is quite complex, and PostgreSQL doesn’t have built-in Chinese tokenization logic. Although there are some third-party extensions like pg_jieba and zhparser, they’re poorly maintained and may not work on newer versions of PostgreSQL.

But this doesn’t prevent us from using PostgreSQL’s infrastructure to implement advanced fuzzy search. Actually, the tokenization logic mentioned above is for extracting summary information (keywords) from large texts (like web pages). Our requirement is exactly the opposite—not only do we not extract and summarize, but we need to expand keywords to achieve specific fuzzy requirements. For example, we can completely include Chinese pinyin, initials abbreviations, and English abbreviations of keywords in the keyword list when extracting application name keywords, or even put author, company, category, and other things users might be interested in. This way, rich input can be used when searching.

Basic Framework#

Let’s first build the framework for solving the entire problem.

- Write a custom tokenization function to extract keywords from names (each character, each two-character phrase, pinyin, English abbreviations—anything can be included)

- Create a functional expression GIN index on the target table using the tokenization function

- Customize your fuzzy search through array operations or

tsquerymethods

-- Create a tokenization function

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION tokens12(text) returns text[] as $$....$$;

-- Create expression index based on this tokenization function

CREATE INDEX ON app USING GIN(tokens12(name));

-- Use keywords for complex custom queries (keyword array operations)

SELECT * from app where split_to_chars(name) && ARRAY['天气'];

-- Use keywords for complex custom queries (tsquery operations)

SELECT * from app where to_tsvector123(name) @@ 'BTC &! 钱包 & ! 交易 '::tsquery;PostgreSQL provides GIN indexes, which can support inverted index functionality very well. The more troublesome part is finding a suitable Chinese tokenization plugin to break down application names into a series of keywords. Fortunately, for this type of fuzzy search requirement, we don’t need semantic analysis as fine as search engines or natural language processing. We can just follow pg_trgm’s approach and manually handle Chinese in a rough way. Additionally, through custom tokenization logic, many interesting features can be implemented, such as pinyin fuzzy search and pinyin initial abbreviation fuzzy search.

Let’s start with the simplest tokenization.

Quick Start#

First, let’s define a very simple and crude tokenization function that just splits input into combinations of 2-character words.

-- Create tokenization function to split strings into arrays of single and double characters

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION tokens12(text) returns text[] AS $$

DECLARE

res TEXT[];

BEGIN

SELECT regexp_split_to_array($1, '') INTO res;

FOR i in 1..length($1) - 1 LOOP

res := array_append(res, substring($1, i, 2));

END LOOP;

RETURN res;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql STRICT PARALLEL SAFE IMMUTABLE;Using this tokenization function, we can break down an application name into a series of morphemes:

SELECT tokens2('艾米莉的埃及历险记');

-- {艾米,米莉,莉的,的埃,埃及,及历,历险,险记}Now suppose a user searches for the keyword “艾米利”, which gets split into:

SELECT tokens2('艾米莉');

-- {艾米,米莉}Then, we can very quickly find all records containing these two keyword morphemes through the following query:

SELECT * FROM app WHERE tokens2(name) @> tokens2('艾米莉');

美味餐厅 - 艾米莉的圣诞颂歌

美味餐厅 - 艾米莉的瓶中信笺

小清新艾米莉

艾米莉的埃及历险记

艾米莉的极地大冒险

艾米莉的万圣节历险记

6rows / 0.38msHere, through keyword array inverted indexes, we can quickly achieve prefix and suffix fuzzy effects.

The condition here is quite strict—applications need to completely contain both keywords to match.

If we use more lenient conditions for fuzzy search, for example, containing any morpheme:

SELECT * FROM app WHERE tokens2(name) && tokens2('艾米莉');

AR艾米互动故事-智慧妈妈必备

Amy and train 艾米和小火车

米莉·马洛塔的涂色探索

给利伴_艾米罗公司旗下专业购物返利网

艾米团购

记忆游戏 - 米莉和泰迪

(56 row ) / 0.4 msThen the candidate set of applications available for further filtering becomes broader. At the same time, execution time didn’t change dramatically.

Furthermore, we don’t need to use completely consistent tokenization logic in queries—we can completely manually perform precise query control.

We can completely control which keywords we want, which we don’t want, which are optional, and which are required through array boolean operations.

-- Contains keywords 微信、红包, but not 支付 (1ms | 11 rows)

SELECT * FROM app WHERE tokens2(name) @> ARRAY['微信','红包']

AND NOT tokens2(name) @> ARRAY['支付'];Of course, returned results can also be ranked by similarity. A commonly used string similarity measure is Levenshtein edit distance—the minimum number of single-character edits needed to change one string into another. This distance function levenshtein is provided in PostgreSQL’s official extension fuzzystrmatch.

-- Apps containing keyword 微信, sorted by Levenshtein edit distance ( 1.1 ms | 10 rows)

-- create extension fuzzystrmatch;

SELECT name, levenshtein(name, '微信') AS d

FROM app WHERE tokens12(name) @> ARRAY['微信']

ORDER BY 2 LIMIT 10;

微信 | 0

微信读书 | 2

微信趣图 | 2

微信加密 | 2

企业微信 | 2

微信通助手 | 3

微信彩色消息 | 4

艺术微信平台网 | 5

涂鸦画板- 微信 | 6

手写板for微信 | 6Improving Full-Text-Search Methods#

Next, we can make some improvements to the tokenization method:

- Reduce keyword scope: Remove punctuation from keywords, exclude modal particles (的得地,啊唔之乎者也) etc. (optional)

- Expand keyword list: Include Chinese pinyin and initial abbreviations of existing keywords in the keyword list.

- Optimize keyword size: Extract and optimize single characters, 3-character phrases, and 4-character idioms. Chinese is different from English—English splits into 3-character substrings work well, but Chinese has higher information density, with single or double characters having great discriminative power.

- Remove duplicate keywords: For example, repeated appearances, or variant characters, synonyms, etc.

- Cross-language tokenization processing. For example, for names with mixed Chinese and Western characters, we can process Chinese and English separately—Chinese, Japanese, Korean characters use Chinese tokenization logic, English letters use regular

pg_trgmprocessing logic.

Actually, these logics aren’t necessarily needed, and these logics don’t necessarily have to be implemented in the database using stored procedures. A better approach would be to read from the database externally, then use specialized tokenization libraries and custom business logic for tokenization, then write back to another column in the data table.

Of course, for demonstration purposes here, we’ll directly use stored procedures to implement a relatively simple improved tokenization logic.

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION cjk_to_tsvector(_src text) RETURNS tsvector AS $$

DECLARE

res TEXT[]:= show_trgm(_src);

cjk TEXT; -- CJK continuous text segments

BEGIN

FOR cjk IN SELECT unnest(i) FROM regexp_matches(_src,'[\u4E00-\u9FCC\u3400-\u4DBF\u20000-\u2A6D6\u2A700-\u2B81F\u2E80-\u2FDF\uF900-\uFA6D\u2F800-\u2FA1B]+','g') regex(i) LOOP

FOR i in 1..length(cjk) - 1 LOOP

res := array_append(res, substring(cjk, i, 2));

END LOOP; -- Add two-character words from each CJK continuous text segment to list

END LOOP;

return array_to_tsvector(res);

end

$$ LANGUAGE PlPgSQL PARALLEL SAFE COST 100 STRICT IMMUTABLE;

-- If you need to use tag array method, you can use this function.

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION cjk_to_array(_src text) RETURNS TEXT[] AS $$

BEGIN

RETURN tsvector_to_array(cjk_to_tsvector(_src));

END

$$ LANGUAGE PlPgSQL PARALLEL SAFE COST 100 STRICT IMMUTABLE;

-- Create tokenization-specific functional index

CREATE INDEX ON app USING GIN(cjk_to_array(name));Based on tsvector#

Besides array-based operations, PostgreSQL also provides tsvector and tsquery types for full-text search.

We can use operations of these two types to replace array operations and write more flexible queries:

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION to_tsvector123(src text) RETURNS tsvector AS $$

DECLARE

res TEXT[];

n INTEGER:= length(src);

begin

SELECT regexp_split_to_array(src, '') INTO res;

FOR i in 1..n - 2 LOOP res := array_append(res, substring(src, i, 2));res := array_append(res, substring(src, i, 3)); END LOOP;

res := array_append(res, substring(src, n-1, 2));

SELECT array_agg(distinct i) INTO res FROM (SELECT i FROM unnest(res) r(i) EXCEPT SELECT * FROM (VALUES(' '),(','),('的'),('。'),('-'),('.')) c ) d; -- optional (normalize)

RETURN array_to_tsvector(res);

end

$$ LANGUAGE PlPgSQL PARALLEL SAFE COST 100 STRICT IMMUTABLE;

-- Use custom tokenization function to create functional expression index

CREATE INDEX ON app USING GIN(to_tsvector123(name));Using tsvector for queries is also quite intuitive:

-- Contains '学英语' and '雅思'

SELECT * from app where to_tsvector123(name) @@ '学英语 & 雅思'::tsquery;

-- All apps about 'BTC' but not containing '钱包' '交易'

SELECT * from app where to_tsvector123(name) @@ 'BTC &! 钱包 & ! 交易 '::tsquery;Reference Articles:#

PostgreSQL Fuzzy Search Best Practices - (Including single character, double character, multi-character fuzzy search methods)