Recently, due to a configuration update released by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike, countless Windows computers worldwide fell into blue screen death, causing endless chaos — airlines grounded flights, hospitals canceled surgeries, supermarkets, theme parks, and industries across the board shut down.

Table: Affected industries, countries/regions, and related institutions (Technical Analysis of CrowdStrike Mass System Crash Incident)

| Industry Domain | Related Institutions |

|---|---|

| Aviation Transport | Flight delays or airport service disruptions in airlines from US, Australia, UK, Netherlands, India, Czech Republic, Hungary, Spain, Hong Kong China, Switzerland, etc. Delta Air Lines, American Airlines, and Allegiant Air announced stopping all flights. |

| Media Communications | Israel Post, French TV channels TF1, TFX, LCI and Canal+Group networks, Ireland’s national broadcaster RTÉ, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Vodafone Group, telecom and internet service provider Bouygues Telecom, etc. |

| Transportation | Australian freight train operator Aurizon, West Japan Railway Company, Malaysian railway operator KTMB, UK rail companies, Australian Hunter Line and Southern Highlands Line regional trains, etc. |

| Banking & Finance | Royal Bank of Canada, Toronto-Dominion Bank, Reserve Bank of India, State Bank of India, DBS Bank Singapore, Banco Bradesco Brazil, Westpac Banking Corporation, ANZ Bank, Commonwealth Bank, Bendigo Bank, etc. |

| Retail | German supermarket chain Tegut, some McDonald’s and Starbucks locations, Dick’s Sporting Goods, UK grocery chain Waitrose, New Zealand’s Foodstuffs and Woolworths supermarkets, etc. |

| Healthcare | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, UK National Health Service, two hospitals in Lübeck and Kiel Germany, some North American hospitals, etc. |

| … | … |

In this incident, many programmers enjoyed discussing which sys file or configuration file crashed the system (CrowdStrike Official Post-mortem), or which company was amateur hour — vendor security companies and client engineers tearing into each other. But in my view, this problem isn’t fundamentally a technical issue but an engineering management problem. What’s important isn’t pointing fingers at who’s amateur, but what lessons can we learn?

In my view, this accident is the joint responsibility of both vendor and client sides — the vendor’s problem: why was a change with such high crash rates rapidly deployed globally without gradual rollout? Was gradual testing and validation performed? The client’s problem: why allow such changes to be pushed online in real-time to their computers without control, placing all endpoint security entirely on supply chain reliability?

Controlling blast radius is a fundamental principle in software releases, and gradual deployment is basic practice in software delivery. Many internet applications use sophisticated gradual release strategies, starting with 1% traffic and gradually scaling up, allowing immediate rollback when issues are discovered, avoiding catastrophic all-at-once failures.

Database and operating system changes follow the same principle. As a DBA who has managed large-scale production database clusters, we’re extremely careful to use gradual strategies when making database or underlying OS changes: first testing changes in Devbox development environments, then applying to pre-production/UAT/Staging environments. After running for days without issues, we begin production releases: starting with one or two edge business systems, then following business criticality classifications A, B, C, and replica/primary sequence and batches for gradual changes.

A head securities firm operations director also shared financial industry best practices in our group — direct network isolation, prohibiting internet updates, buying Microsoft ELA, setting up patch servers on internal networks, then tens of thousands of terminals/servers uniformly updating patches and virus definitions from patch servers. Gradual approach: each branch office and business department selects one or two machines as gradual environment, running for a day or two without issues, entering large gradual environment for a full week, then final production environment split into three waves updating once daily, completing the entire release. For emergency security events — the same gradual process applies, just compressing the time cycle from one-two weeks to several hours.

Of course, some vendor security companies and security-background engineers might offer different perspectives: “Security industry is different, we need to race against viruses,” “when virus researchers discover new viruses, then determine how to defend the entire network fastest,” “when viruses come, my security experts judge activation needed, no time to notify you,” “blue screens are better than losing digital assets or being randomly controlled.” But for clients, security is an entire system — delaying configuration gradual releases isn’t a big deal, but concentrated batch crashes are unacceptable shocks.

At least for enterprise customers, whether to update, when to update — this risk-benefit assessment should be made by clients, not vendors making arbitrary decisions. Clients who abandon this responsibility, unconditionally trusting vendors for over-the-air updates, are also amateur hour. Security software is legitimized large-scale botnet software — even with users’ maximum goodwill trusting vendors lack malicious intent, it’s hard to avoid disasters from careless mistakes and arrogant stupidity (like this Blue Screen Friday).

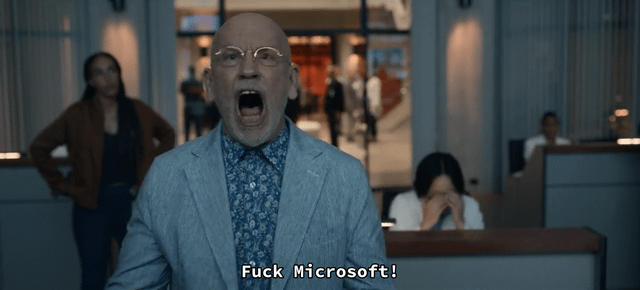

(US TV series “Space Force” famous meme: Emergency mission encounters Microsoft forced update)

If your system is truly important, before accepting any changes and updates, remember — Trust, But Verify. If vendors don’t provide the Verify option, you should decisively say no within your authority.

I believe this incident will greatly benefit “local-first software” philosophy — local-first doesn’t mean no updates, no changes, using one version until the end of time, but being able to continuously run on your own computers and servers without internet connectivity. Users and vendors can still upgrade functionality and update configurations through patch servers and periodic pushes, but the timing, method, scale, and strategy of updates should be user-specified, not vendors overstepping to make decisions for you. I believe this is the true essence of “autonomous and controllable” concepts.

In our own open-source PostgreSQL RDS, database management software Pigsty, we’ve always practiced local-first principles. Whenever we release a new version, we snapshot all software to be installed and their dependencies, creating offline software installation packages, allowing users to easily achieve highly deterministic installations without internet access or containers. If users want to deploy more database clusters, they can expect consistent versions in their environment — meaning you can freely remove or add nodes for metabolism, keeping database services running until the end of time.

If you need to upgrade software versions and apply patches, add new version software packages to local software sources and use Ansible playbooks for batch updates. You can choose to run old EOL versions until the end of time, or update and try the latest features the moment they’re released. You can follow software engineering best practices for gradual releases, but if you really want to go rough-and-fast with one-shot full deployment, that’s also fine. We only provide default behaviors and practical tools, but ultimately, this is users’ freedom and choice.

As the saying goes, extremes lead to reversal. In the current era of SaaS and cloud services dominance, single-point risks and vulnerabilities of critical infrastructure failures become increasingly prominent. I believe after this incident, local-first software philosophy will receive more attention and practice in the future.